The film has a jazz soundtrack. In the 1950s Dave Brubeck, the well-known jazz pianist, who died a few days ago, was one of the so-called Jazz Ambassadors touring for the State Department. Also booked to tour as Jazz Ambassadors were legendary African American jazz musicians like Louis Armstrong.

The State Department honchos believed that creating and funding tours which included black jazz musicians would show the world the great equality-driven democracy the U.S. epitomized in the 1950s. The tours were intended to counter the racist, Jim Crow profile that the rest of the world saw in American society at the time.

In 1958, Louis Armstrong refused to tour for the State Department and publicly decried President Eisenhower's lack of support for school integration in the south. Such was the social climate of the 1950s when this film was made.

Here is what Wikipedia posted about the film:

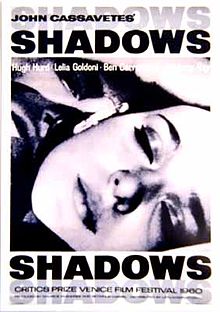

SHADOWS

is an

improvised film about interracial relations during the Beat Generation years in

New York City, and was written and directed by

John Cassavetes. The film's stars are Ben Carruthurs, Lelia Goldoni,

Hugh Hurd, and Anthony Ray (Tony in the

film). Many film scholars consider Shadows one of the historical highlights of independent film festival developments in the U.S. In 1960 the film won the

Critics Award at the Venice Film Festival.

Cassavetes

shot the film twice, once in 1957 and again in 1959. The second version is the

one Cassavetes favored. Although he did screen the first version, he lost track

of the print, and for decades it was believed to have been lost or destroyed.

The 1957 version was intended to have the jazz music of bassist, Charles

Mingus on the soundtrack, but Mingus failed to meet various deadlines set by

Cassavetes. The contributions of saxophonist Shafti

Hadi, the saxophonist for Mingus's group, proved to ultimately be the

soundtrack for the film.

In 2004,

after over a decade of searching, Cassavetes scholar and Boston University

professor Ray Carney announced his discovery of the

only print of the original version of the film, found in a box on the subway

before being bought with some other "lost and found" objects. See an article below from Slate which casts a shadow on Ray Carney's dealings with the work of other filmmakers in addition to Cassavetes. The film

Carney managed to find was a pristine copy that apparently had only been

screened two or three times before it was lost. Carney has posted three video

clips from Shadows I for viewing on his website to verify the film's

condition and indicate the presence of a complete credits sequence, which

demonstrates that the version he possesses is a final version, not a rough

assembly.

Film

critic Leonard Maltin calls

Cassavetes' second version of Shadows "a watershed in the birth of

American independent cinema". The movie was shot with a 16 mm handheld

camera on the streets of New York. Much of the dialogue was improvised, and the

crew were class members or volunteers. The jazz-infused score underlines the

movie's Beat Generation theme of alienation

and raw emotion. The movie's plot features an interracial relationship, which

was still a taboo subject in Eisenhower-era America.

In

1993, Shadows was selected for preservation in the United States National Film

Registry

by the Library of Congress as being

"culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".

For Ray Carney's description of his hunt for the missing Shadows first copy click on this link:

For Ray Carney's description of his hunt for the missing Shadows first copy click on this link:

http://people.bu.edu/rcarney/discoveries/shadowsquest.shtml

Did This Film Scholar Steal the Work of a Beloved Indie Filmmaker?

Did This Film Scholar Steal the Work of a Beloved Indie Filmmaker?

|

Posted Tuesday, Oct. 16, 2012, at 3:21 PM ET

The Rate My Professors page for Boston University’s Ray Carney seems particularly divided, even for that contentious forum. It contains superlatives that range from “the most intelligent, thoughtful, and motivating figure I’ve ever encountered in my life” to "Worst Professor."

However, Carney’s student critics are the least of his worries right now. The film scholar has provoked the outrage of movie critics and enthusiasts by confiscating endangered works and production materials from beloved independent filmmaker Mark Rappaport. Rappaport, director of The Scenic Route (“a movie of great, grave, tightly controlled visual daring,” according to Roger Ebert) and From the Journals of Jean Seaberg (a “new kind of movie, and a highly entertaining one,” says Jonathan Rosenbaum) among many other works, issued a plea to the international film community in September to rescue his films from the scholar’s possession. According to his letter, Rappaport entrusted digital copies, video masters, and script drafts, among other materials, to Carney—who has in the past called Rappaport “the best-kept secret in American film” and “a genuine national treasure”—when he moved from the U.S. to France in 2005. However, when Rappaport contacted Carney this past April to return his property, Carney did not respond to his emails—or, later, to a court’s preliminary injunction. When the court entered a default against the scholar for Carney’s failure to respond to the charges, Carney hired a lawyer who claimed Rappaport gave him the rare materials as a gift. After a four month-long court battle, Carney contacted the director, saying he would return the materials if Rappaport gave him $27,000 for the trouble of keeping the materials for seven-and-half years. Rappaport did not continue the suit, citing its expense.

In the letter, Rappaport pleads, “Without the digital video masters, my films, everything prior to 1990 … cannot be made available for streaming, commercial DVDs, video-on-demand, or any electronic delivery system down the road. My life as a filmmaker, my past, and even my future reputation as a filmmaker are at stake.”

Carney, a powerful and influential scholar who has been deemed “a cinematic Ralph Nader,” has gotten into a fight over film possession before: He feuded with John Cassavetes’ widow Gena Rowland over his discovery of a first cut of Shadows (the result of a 17-year quest), which he claims is an improvised work and therefore does not belong to her company, Faces Distribution Incorporated. Reporting on that conflict, GreenCine Daily referred to Carney’s “eerie insistence on speaking on behalf of Cassavetes himself.”

Carney has long maintained an extensive website devoted to his work, and his past comments there are not helping him now. When Carney was emailed by someone looking for Rappaport’s contact information so that he could put together a screening of some of Rappaport’s old films, he published the exchange on his webpage. “Mark is a great friend and gave me almost everything he owned when he left New York for France,” Carney explained, “Thousands of pages and box after box of material. So I am now the ‘Mark Rappaport Archive.’” He then said that he is “not a rental operation” and so his “massive collection is of no use at all for your purposes.” “Sorry I can’t help or be more encouraging,” he added. As Roger Ebert tweeted this past September, “Yeah, sure, indie director Mark Rappaport ‘gave’ his life work to Prof. Ray Carney.” Ebert has called the whole Carney/Rappaport business a “disturbing story.”

Former supporters of Carney have since turned against the scholar in Rappaport’s defense, including Jon Jost of cinemaelectronica, who recently published a petition for Carney to return Rappaport’s “stolen film materials.” Jost, a self-avowed friend of Carney’s, writes that many attempts to contact his former email correspondent have gone unanswered, confirming his suspicions that Carney’s intentions are less than trustworthy.

Meanwhile, Carney has not responded to the increasing noise level on Internet forums to defend himself over the Rappaport works and is reportedly spending time in Vermont. He can’t be missing in action forever, though. He should be back at Boston University’s College of Communication in Spring 2013, to teach “American Independent Film.”

No comments:

Post a Comment